The Japanese American Museum of Oregon

Remembering Minidoka

With the help of an Oregon Lottery-funded grant, a Portland museum will help Oregonians remember a time of racial hysteria and injustice. And, by remembering, we can hope to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

December 7, 1941

Oregonians woke up that Sunday thinking it was just another day. Before it was over, it became clear that it was the day that changed everything — the day that the Japanese attacked the naval base at Pearl Harbor, finally drawing America into WWII. A day that will live in infamy.

Oregonians woke up that Sunday thinking it was just another day. Before it was over, it became clear that it was the day that changed everything — the day that the Japanese attacked the naval base at Pearl Harbor, finally drawing America into WWII. A day that will live in infamy.

For families of Japanese descent living on America’s west coast, the attack on Pearl Harbor meant that and so much more. For them, it marked the beginning a time when they were targeted for harassment and hate, not because of anything they had done, but because they resembled the people who had become America’s enemy. Although most were peaceful farmers or small business owners, they immediately came to be viewed as potential spies and terrorists for the Japanese Empire.

The hysteria came to a crescendo when President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, clearing the way for their removal to what he called “concentration camps” (and what today we more euphemistically call “internment camps”) in some of the harshest corners of the country.

In Oregon, our Japanese neighbors lost farms and family businesses. They lost their sources of income. They lost homes when they could no longer pay their mortgages. They lost family heirlooms and any possessions they couldn’t quickly sell or carry with them. When their imprisonment ended with the war, they had little means to return to Oregon and start over. Many relocated to other, more welcoming parts of the country.

In Oregon, our Japanese neighbors lost farms and family businesses. They lost their sources of income. They lost homes when they could no longer pay their mortgages. They lost family heirlooms and any possessions they couldn’t quickly sell or carry with them. When their imprisonment ended with the war, they had little means to return to Oregon and start over. Many relocated to other, more welcoming parts of the country.

Perhaps worst of all, fully 70% of those imprisoned were American-born, U.S. citizens. Even though they were never charged with any crimes, they were incarcerated for the duration of the war, subjected to loyalty tests, and denied the protections every citizen should expect under the U.S. Constitution.

Japanese-American Incarceration

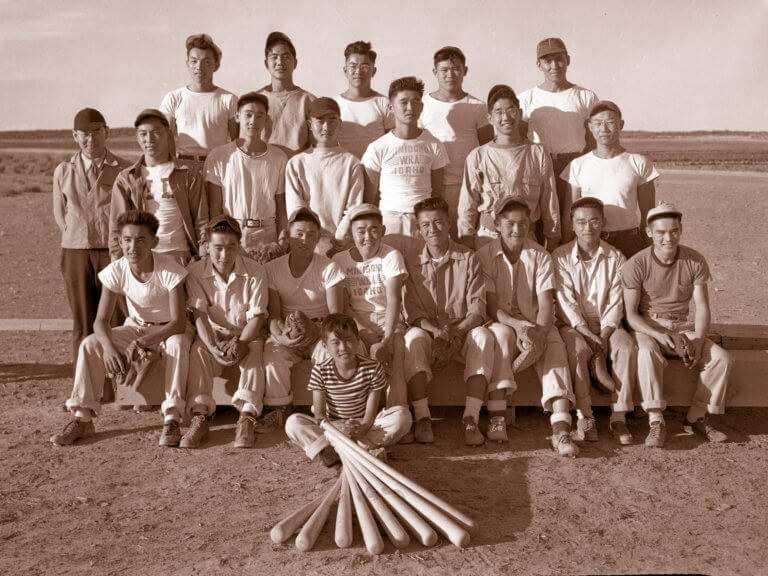

After reporting to temporary assembly centers, most of Oregon’s Japanese residents were eventually sent to a “camp” in the southeast corner of Idaho. Christened “Minidoka,” the facility consisted of many tarpaper barracks and administrative buildings behind barbed wire. Despite the desolation, inmates did their best to recreate normalcy in their daily activities. They remained confined to this barren landscape until the war’s end.

Thanks in part to a Lottery-funded State Heritage Grant, the Japanese American Museum of Oregon will make access to many of the documents and artifacts in its Minidoka collection available online.

Minidoka Today

More than 40 years after World War II, Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties act of 1988 into law, apologizing to those incarcerated and providing nominal reparations for the losses they’d sustained. The legislation made clear that the imprisonment of America’s Japanese residents and citizens had been based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

Today, what’s left of Minidoka itself is carefully preserved as a National Historic Site under the management of the National Park Service. The physical site in Idaho, along with collections like those being preserved by our own Japanese American Museum in Portland, will help ensure that our nation always remembers a dark period when we were blinded by racial hatred and, hopefully, help us strive to do better in the future.

Our thanks to Densho.org for their work in providing an extensive, digitized archive of materials related to Japanese-American incarceration, including access to the public domain photos included here. For more information, visit Densho.org.

Portland’s Japanese Language Newspaper

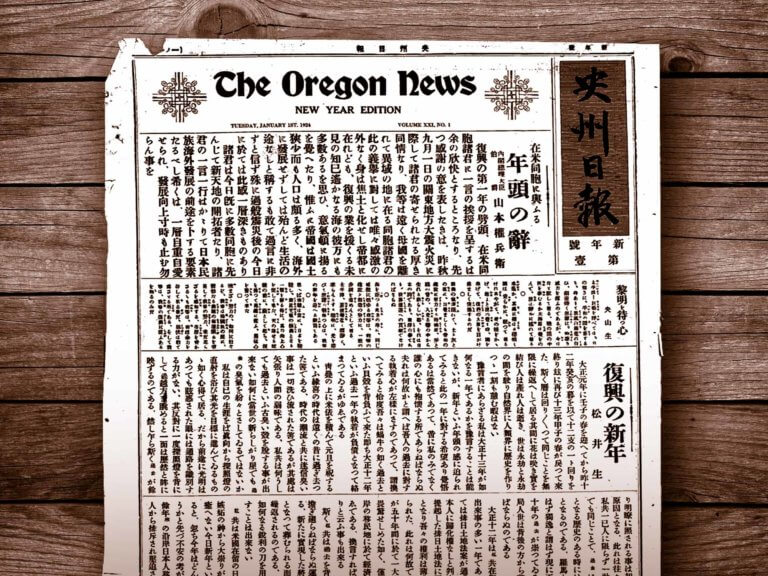

In addition to their important work in preserving the Minidoka experience, the Japanese American Museum also received an earlier lottery-funded grant to translate and preserve Nihonmachi’s Japanese language newspaper, the Oshu Nippo.

Portland’s Nihonmachi (or Japan town) published its own newspaper for many years. Ten of the earliest issues (from 1918–1925) were preserved in the Museum’s collection, but that didn’t mean they were especially accessible to researchers. Not only were they published in Japanese, but they employed an older style of Japanese that is no longer used by modern speakers. The issues needed to be transcribed, translated into modern Japanese, and then translated again into English before being digitized and published online. These efforts took a team of translators from Portland and its sister city Sapporo working closely together for more than a year to complete the project.

Featured Projects

Featured Games

LOTTERY DOLLARS DOING GOOD THINGS IN YOUR COMMUNITY

Economic Growth

State Parks

Outdoor School

Natural Habitats

Public Schools